In the summer of 2018, several Japanese children came to Tsukuba International Christian Assembly* for an English camp where they had the chance to take part in fun activities while learning English. Their parents sent them to the camp because they believed that learning English would help their children in life.**

One day, after playing some fun group games, Erin McCoin noticed that several of the kids seemed upset.

“Is everything alright? Are you okay?” she asked one young boy. Let’s call him Kosei.

“I’m not good,” Kosei responded with tears. “I’m not good.” He was upset because he hadn’t won the game.

As a Japanese child, Kosei was being raised in an honor-shame culture in which success brings honor to one’s family while failure brings shame upon the family. The need to be perfect was second nature to him. He knew it was his duty and obligation to bring honor to his family — failure was unacceptable. And public failure was shameful.

So when Kosei didn’t win the game — when he wasn’t successful — his shame spilled over into tears.

In addition to feeling the pressure of his family to succeed, Kosei also has to battle the pressure of his friends and school classmates to conform to accepted behavior. He is always in danger of being ignored, shoved, or teased by his classmates if he is different in any way from them.

The Embodiment of Japanese Culture

Kosei is a metaphor for the challenges and struggles faced by Japanese children and youth — he finds his worth and value in succeeding, striving for perfection, and behaving in ways that don’t dishonor his family. At the same time, like most Japanese children and youth, Kosei finds safety in conformance to the behavior of his peers.

It’s an impossible scenario. Kosei’s family expects perfection. His school expects excellence. His classmates expect conformance (which includes not being better than them, in contrast to his family’s and his school’s expectations).

Where will Kosei find meaning? How will Kosei know that he has value and purpose? Who will give Kosei hope?

When children and teenagers fail to live up to all the expectations put on them — when they are less than perfect — the results are not surprising: shame, anxiety, depression, despair, and hopelessness begin to take hold in their lives. If not addressed, these challenges will continue to grip their souls into adulthood.

And their search for hope can lead to unhealthy obsessions and even tragic results:

Oyayubibunka

A majority of Japanese youth seek to find self-worth in social friendships, whether such friendships develop through face-to-face relationships or as is more common today, through their smartphones.

According to a February 2016 survey, 70.6 percent of Japanese youth between the ages of 10 and 18 own a smartphone. Boys in fourth through sixth grades use their smartphones 1.8 hours per day, and girls use them 1.7 hours per day. In junior high, those figures increase to 2.0 hours per day for boys and 2.1 hours per day for girls. High school students increase their daily usage even further — 4.8 hours per day for boys and 5.9 hours for girls. Four percent of high-school-aged girls in Japan use their smartphones 15 hours per day or more.1

Smartphone usage is so prevalent and so embedded in Japanese youth culture, that a term has been coined to describe the obsession — oyayubibunka (literally, “thumb culture”).

Japanese teens use their smartphones to watch television and video, listen to music, play games, take and share photos, record and share videos, access the internet, and chat with friends.2 When they chat, they share media — and it’s the funniest and most visually appealing content which gets shared.3

All of this digital activity, however, does not ultimately lead to them understanding the worth they have in God’s eyes. According to a survey conducted by the Japan Youth Research Institute, only 36 percent of Japanese students believe they are valuable.4

Not finding self-worth in social friendships (whether via smartphones or face-to-face friendships), some Japanese youth instead turn inward to an extreme extent.

Hikikomori

In Japan, it is estimated that 3 million people are hikikomori — people who have been so severely bullied in school or at work that they decide they can’t cope with being among people any longer. They decide that withdrawing, locking themselves in a room in their parents’ house, and playing video games all day is the best solution to coping with their emotional struggles. Although they still may not find an assurance of their value, at least they are free from the buffeting they receive at the hands of others.

Their parents don’t want to admit that their children have a problem because doing so would bring shame on the family, and so it’s difficult for the hikikomori to receive the help they need.

Media may be the only way of reaching them with the love of Jesus.

Even more tragically, other Japanese youth find a different way to cope with failure.

Jijatsu

Japan has an exceptionally high rate of suicide (jijatsu in Japanese). It is the leading cause of death in men between the ages of 20 and 44 and in women between the ages of 15 and 34.5

Assemblies of God missionary to Japan Christopher L. Carter says, “In Japan, there’s this constant pressure from society to succeed and to be what you’re expected to be. And when people are unable to live up to the expectations put upon them, they see suicide as a solution to that problem. If you’re in middle school and you can’t pass the test to get into high school, suicide is a solution. If you’re in high school and you can’t pass the test to get into university, suicide is a solution. If you can’t get ahead at your job or you get fired or you can’t pay back the loan shark, suicide is a solution … Suicide is seen as a legitimate solution to a really bad problem.”6

Hopelessness

Unfortunately, Japanese youth are not looking for solutions to their hopelessness in the right places.

Only 10 percent of Japanese people believe in the existence of a personal God. Only 50 percent say they have ever desired help from God or gods. Less than 0.3 percent of the Japanese population in Japan is evangelical. They are the second largest unreached people group in the world.7

The land of the rising sun is in desperate need of the healing that only the sun of righteousness brings.8

Liberty for the Captives

Jesus offers freedom to Japanese children who are enslaved by unreasonable expectations, shame, anxiety, depression, despair, hopelessness, and isolation. The gospel message tells Japanese youth of God’s grace that forgives us for our failures, of Jesus’ death that delivers us from shame, of the life of Jesus that fills us with joy and frees us from anxiety and depression, of the hope of eternal life that relieves our despair and hopelessness, and of the community of God’s people that provides us with a family.

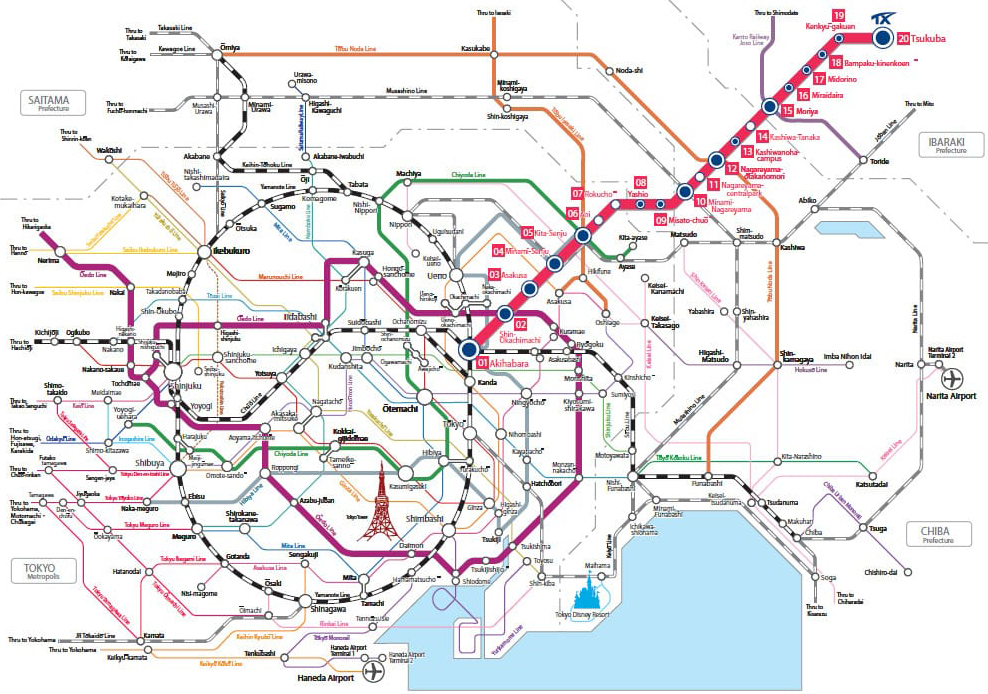

Tsukuba

One city where the message of God’s grace and the freedom found in Jesus is desperately needed is Tsukuba, Japan. Tsukuba — known as the science city of Japan — is home to over 21,000 children between the ages of 0 and 9 and over 22,000 children and teenagers between the ages of 10 and 19.9

Over 43,000 children and teenagers, most of whom have never heard about the love of Jesus.

Who will tell the children of Tsukuba about Jesus and the gospel message? Who will go to the youth of Tsukuba and tell them of the freedom from shame that is available to them through relationship with Jesus?

Josh and Erin McCoin

Josh and Erin McCoin have answered God’s call to take the news of Jesus’ love to the 43,000 Kosei’s who live in Tsukuba!

Growing up, Erin was a victim of mental and emotional abuse, feeling tremendous pressure from her parents to be perfect. She believed that if she could just be good enough, if she could behave perfectly, then she could earn her parents’ love.

When she was sixteen years old, a friend of hers invited her to a church youth camp. She agreed to go to the camp with her friend — to get away from her parents. But at the camp, she learned about God’s love and how He is perfect. And that He takes our shame and loves us despite our failures. When Erin committed her life to Jesus at the camp, she felt that God was calling her to be a missionary.

At Campbellsville University, she met Josh. Josh had grown up in a Christian home, and he was studying Mass Communication with an emphasis in Broadcast and Digital Media. Erin was studying Christian Missions, Educational Ministries, and Teaching English as a Second Language.

During her second year, she had two Japanese roommates who told her about the hopelessness in their country. This confirmed Erin’s growing conviction that Japan was the country to which God was calling her.

“I still struggle with (a) perfectionist mindset sometimes,” Erin says, “but as I felt the call to missions and to Japan, I knew that God was going to redeem my past. He was going to use the bad that happened to me to help me relate to the youth of Japan who feel overwhelmingly hopeless and as if they have to be perfect too.”

Josh and Erin took a Global Christianity class together and chose Japan as the topic for their class project. While working on the project, they read in the book Operation World that 85 percent of youth in Japan do not know why they exist and that 11 percent wish they had never been born. When he read this, Josh’s heart was broken and burdened for Japanese children and youth.

In Erin’s senior year, she received an email “out of the blue” from a department within Assemblies of God World Missions called the Asia Pacific pipeline (they still aren’t sure exactly why the email was sent to them, but they are glad it was). The email’s subject line was “Do You Want to Teach English in Japan?” Josh remembers this and laughingly says, “Yes, that’s exactly what we want to do!”

Through that initial email, Josh and Erin were connected with Chris and Lindsey Carter who are the team leaders of a church-planting team that has become affectionately known as “Team TICA” (“TICA” stands for “Tsukuba International Christian Assembly”).

Josh describes the feeling they had when they arrived in Japan for the English camp in the summer of 2018: “There was such a sense of calm and peace. We knew this was where we were supposed to be.”

Because of their life experience and talents, Josh and Erin McCoin are uniquely qualified to take the message of healing that Jesus offers to the 43,000 children and teenagers of Tsukuba.

Erin’s background gives her a deep understanding of the hopelessness that Japanese youth and children feel. And Josh’s media skills allow him to develop tools for reaching Japanese children and youth through the digital arena in which they spend a large majority of their time.

Join the McCoins!

Josh and Erin McCoin have answered God’s call to take the news of Jesus’ love to the 43,000 Kosei’s who live in Tsukuba. It only remains for us to send them!

If you’ve read our pillar articles (which can be reached through the tabs at the top of the site if you are using a desktop or the three-bar/”hamburger” menu if you are using a mobile device), you know that our conviction is that all believers should be part of a team seeking to reach the unreached. Some will go, some will pray, some will provide financial support, some will provide logistical support.

Here are four ways you can be a part of Josh and Erin’s team:

- You can pray for Josh and Erin on an ongoing basis. The best way to stay informed of their prayer needs is by subscribing to their newsletter at their website or following them on Facebook.

- You can support Josh and Erin financially by signing up to support them on a monthly basis or to contribute a one-time gift at their online giving page. Erin also makes Kumihimo bracelets to raise funds. Contact Josh and Erin for more information — you can find complete contact information at their website.

- You can consider physically joining Josh and Erin to aid the work in Tsukuba. Contact them on Facebook for more information.

- If you are a pastor or missions leader in your church, we would encourage you to get in touch with Josh and Erin to see how they might be able to encourage your people for the cause of children and youth in Japan and also to find out how you can be of service to them.

COUNTRIES IN THIS ARTICLE: Japan

WORKERS IN THIS ARTICLE: Josh and Erin McCoin, Chris and Lindsey Carter

* https://www.tsukubachurch.com

** While the basic event of the boy losing the game, Erin asking him if he was okay, and him saying that he was not “good” as a result are true, the name we’ve chosen for the boy and the rest of his story are fictional.

1 Ishikawa Yūki, Smartphones and Teens: Consumed by Connectedness, Nippon.com, February 28, 2017, https://www.nippon.com/en/currents/d00292/.

2 Toshie Takahashi. Japanese Youths Engaging with Mobile ICTs: Looking ahead from the Past Ten Years, Toshie Takahashi Official Website, November 13, 2013, https://blogs.harvard.edu/toshietakahashi/2013/11/13/hello-world/.

3 Ishikawa Yūki, Ibid.

4 Japanese Teenagers, Youth and Young Adults: Attitudes, Apathy and New Lifestyles, accessed August 5, 2020, http://factsanddetails.com/japan/cat18/sub118/item622.html.

5 Suicide Rate By Country 2020, accessed July 26, 2020, https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/suicide-rate-by-country.

6 TEAM TICA Q&A/Testimonies 3.23.20, accessed July 25, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/canavaninJapan/videos/227907908418811/.

7 Jason Mandryk, Operation World (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2010), locations 25752-26053.

8 Malachi 4:2

9 Tsukuba (Ibaraki), accessed July 28, 2020, https://www.citypopulation.de/php/japan-ibaraki.php?cityid=08220

Leave a Reply